Finding Mandelbrot images to use as video conference background

Motivation

More than thirty years ago an exhibition in London changed how I view the world.

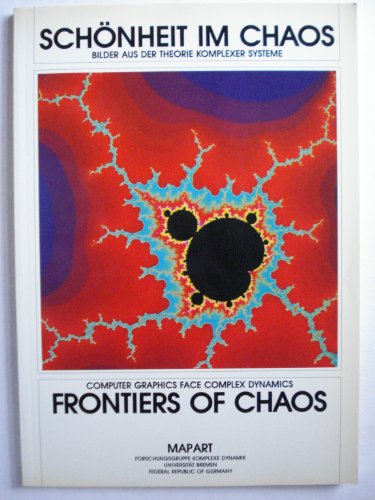

It was called “Schönheit im Chaos / Frontiers of Chaos”, presented by the Goethe-Institut, the German cultural organization. I still have the exhibition book by H.O. Peitgen, P. Richter, H. Jürgens, M. Prüfer, and D.Saupe

It upended what I thought I knew about mathematics. It was astounding how much complexity could emerge from extremely basic calculations.

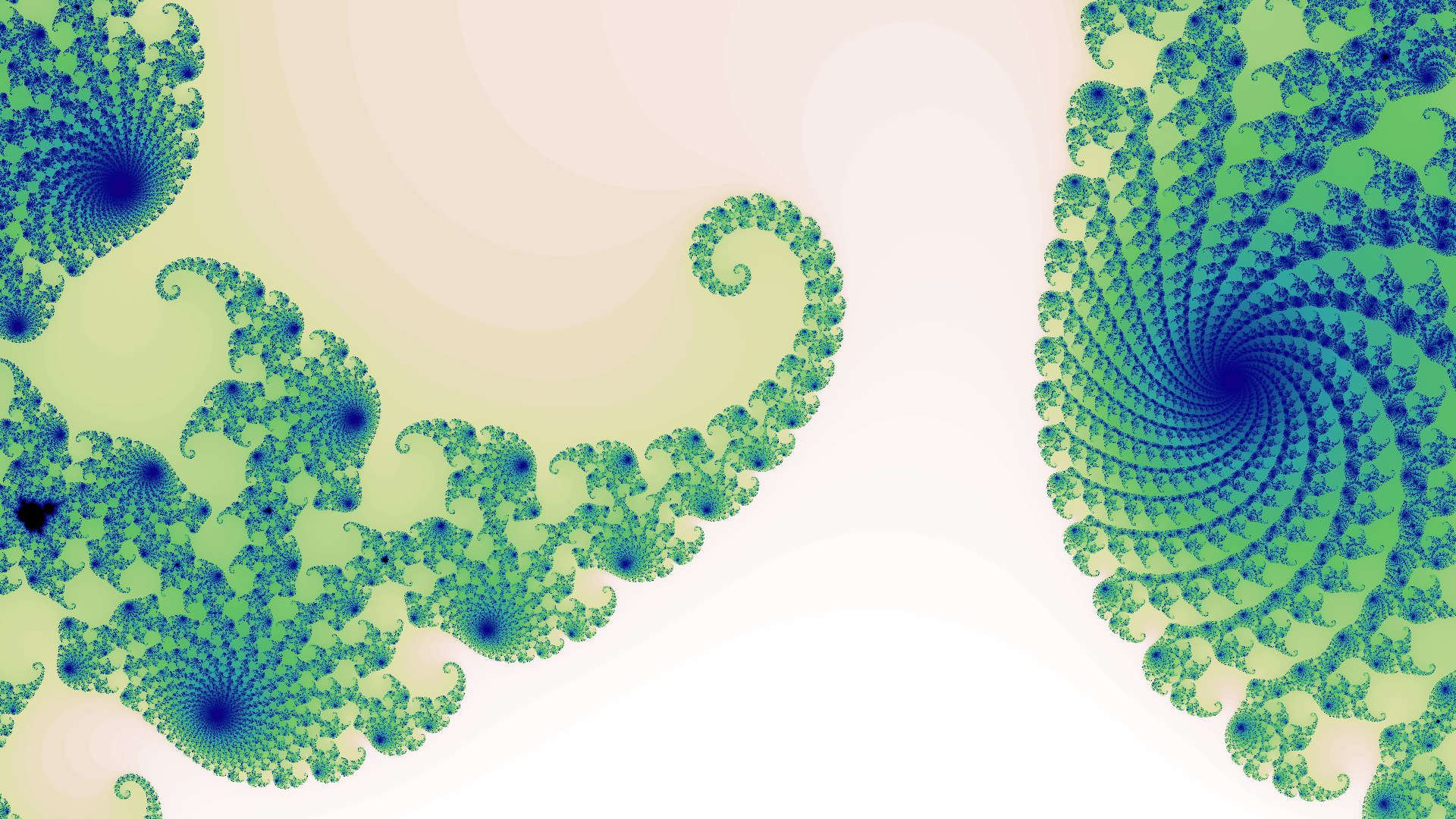

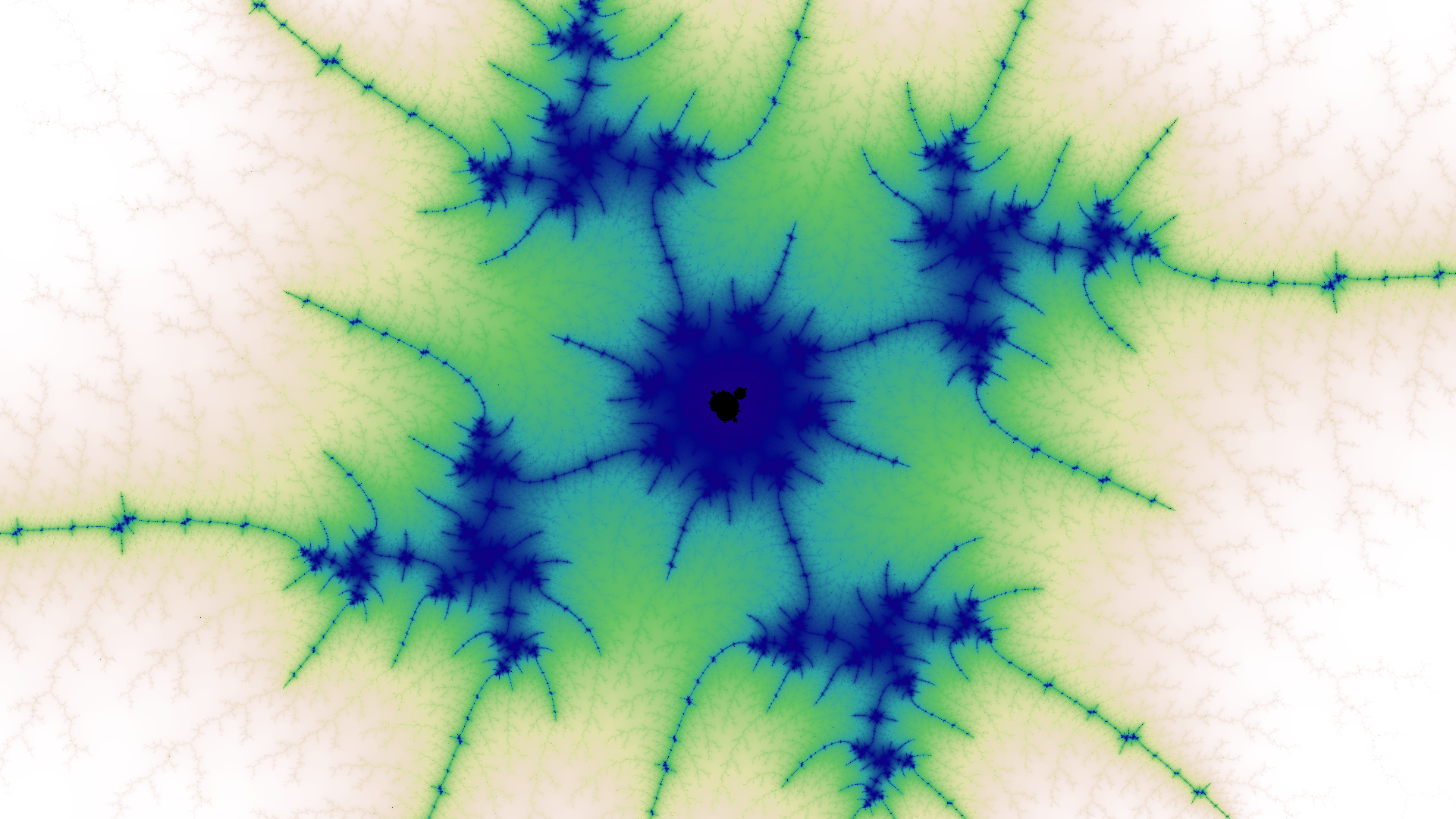

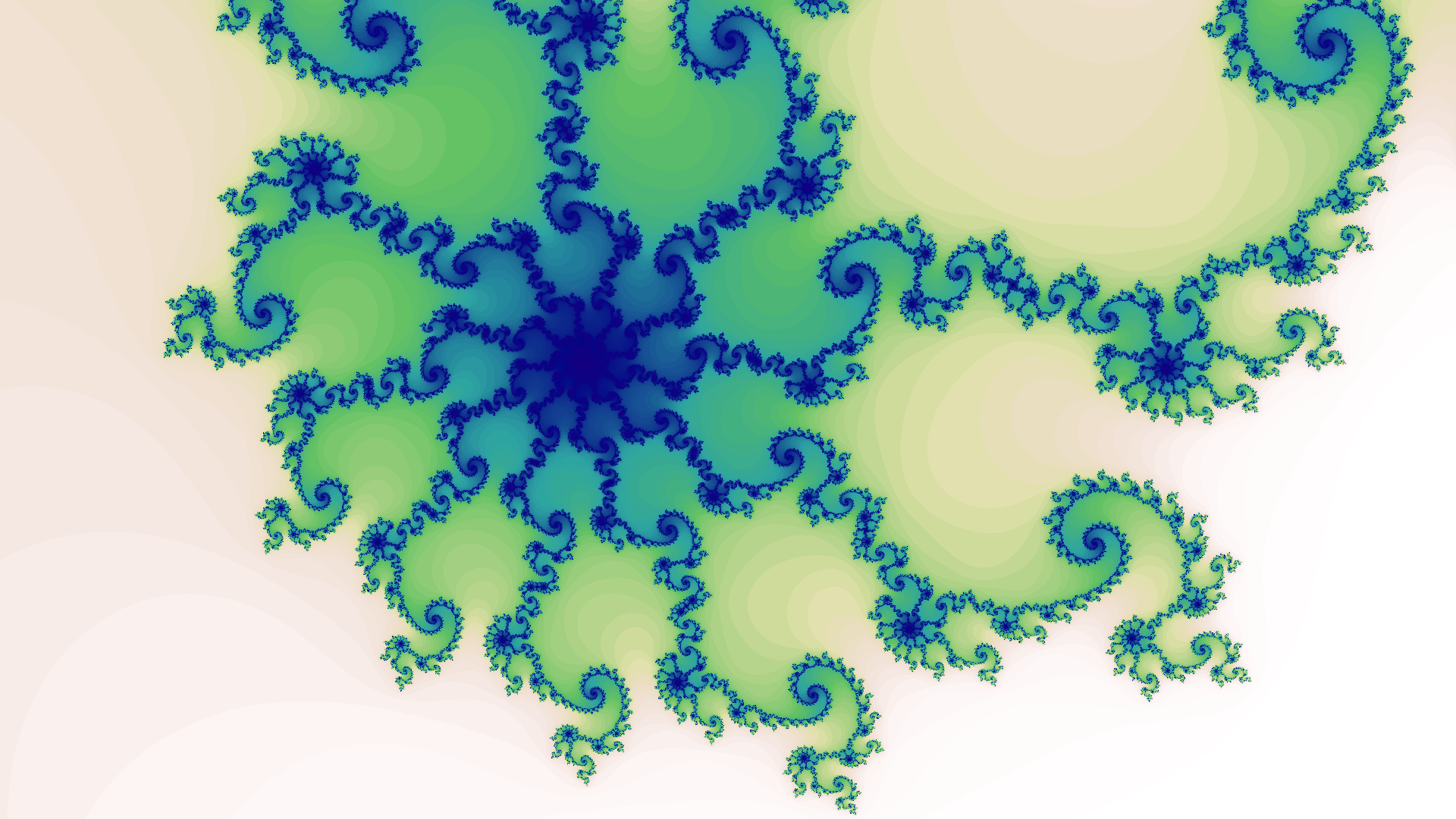

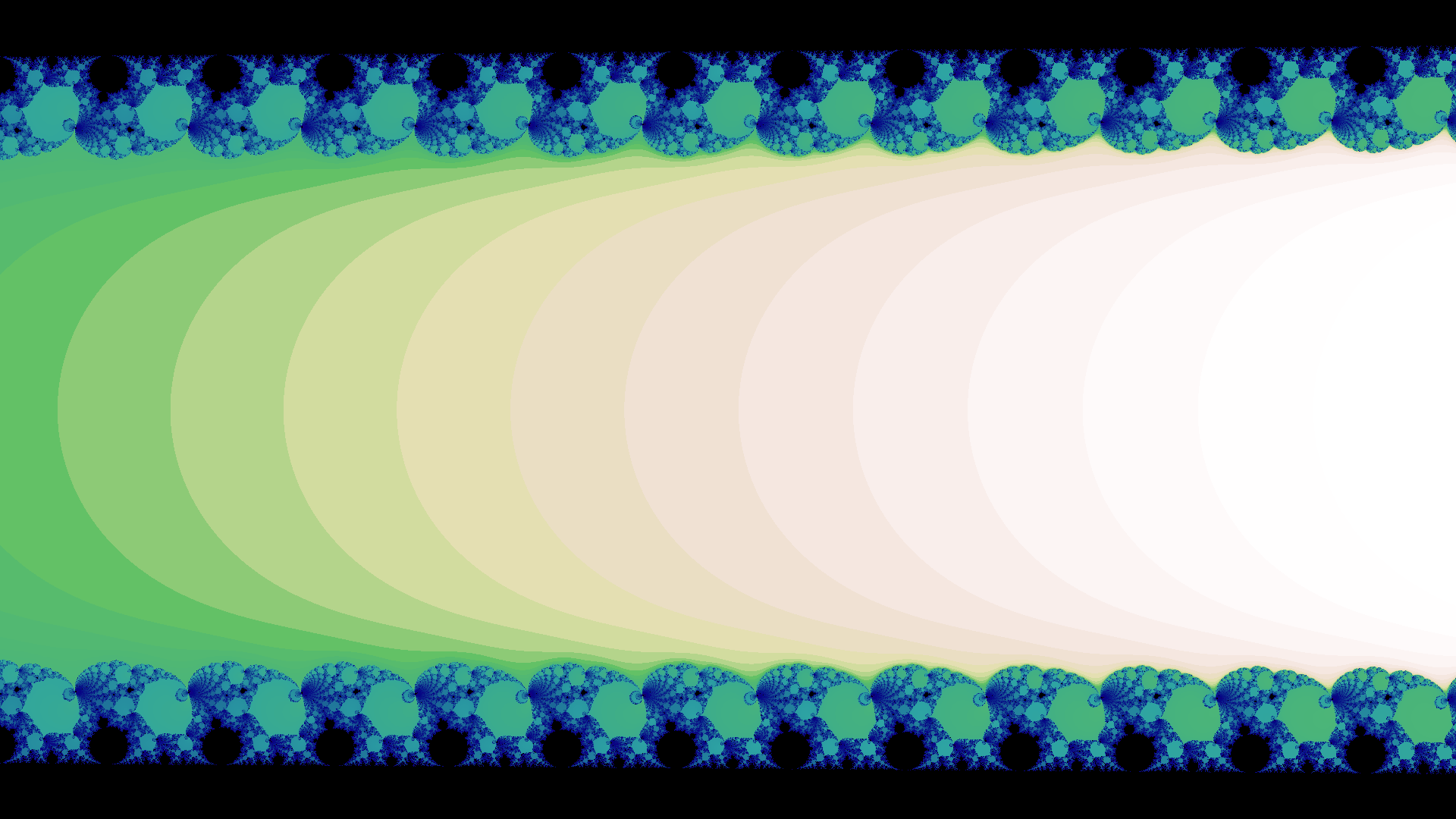

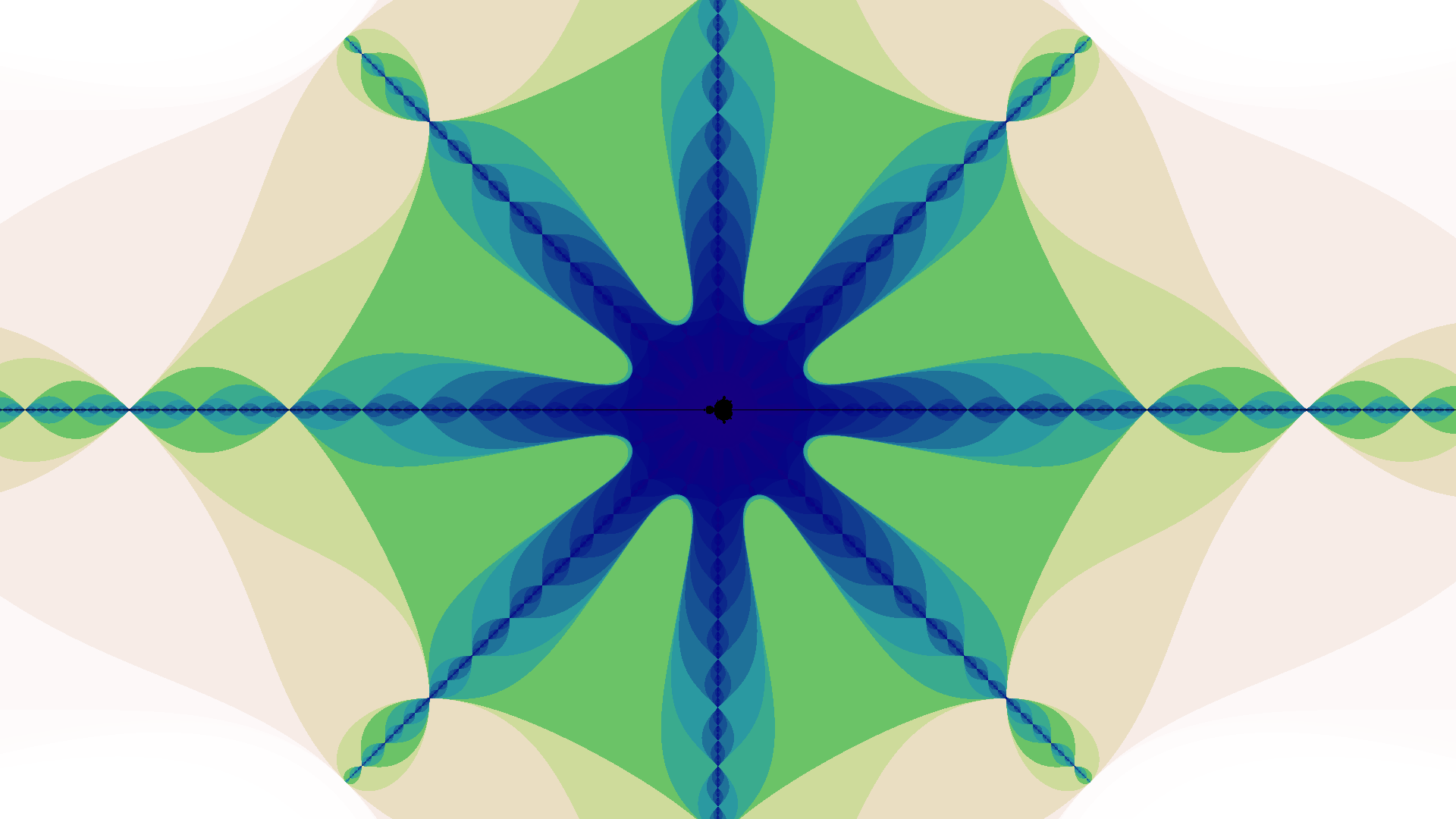

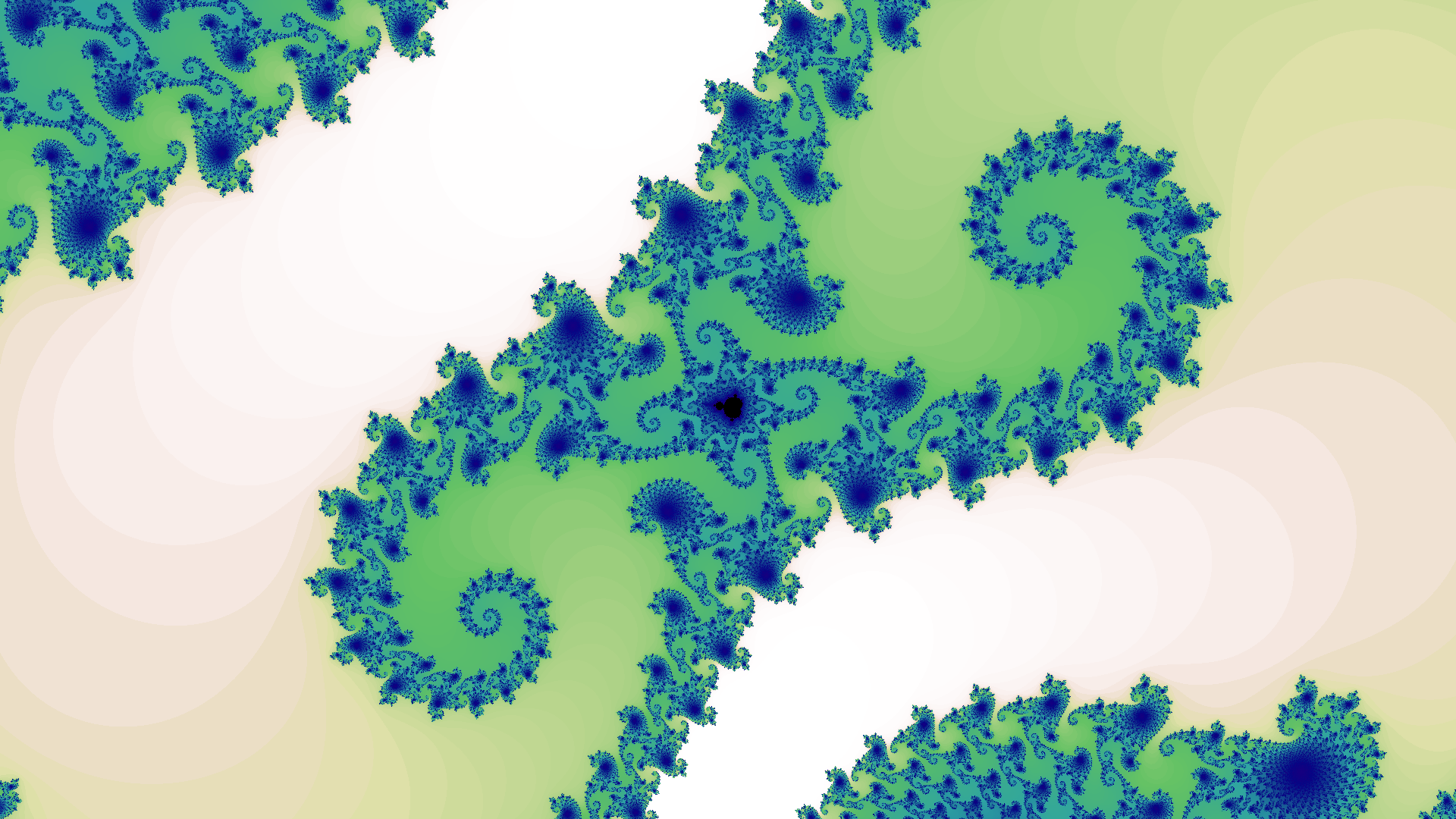

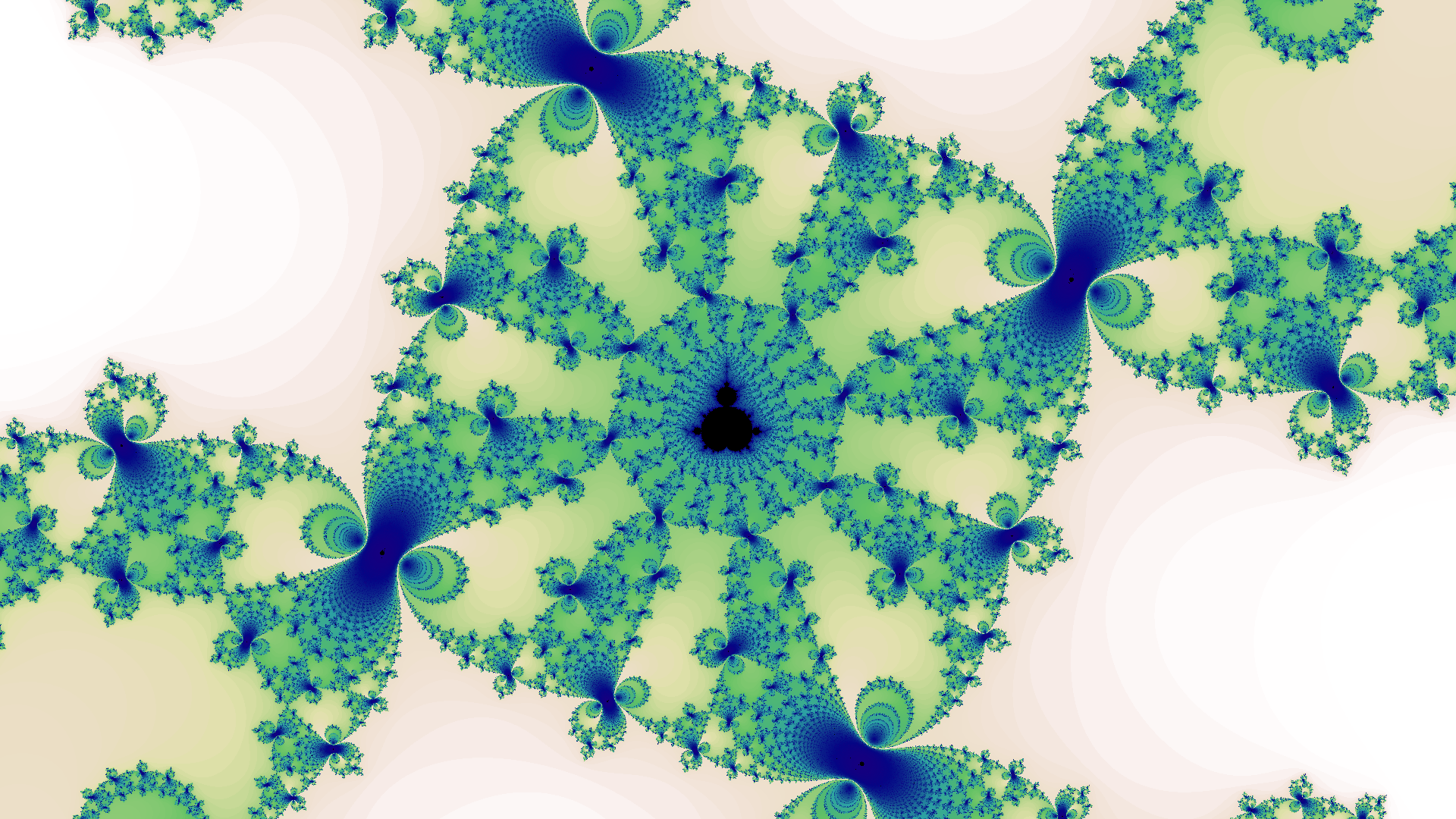

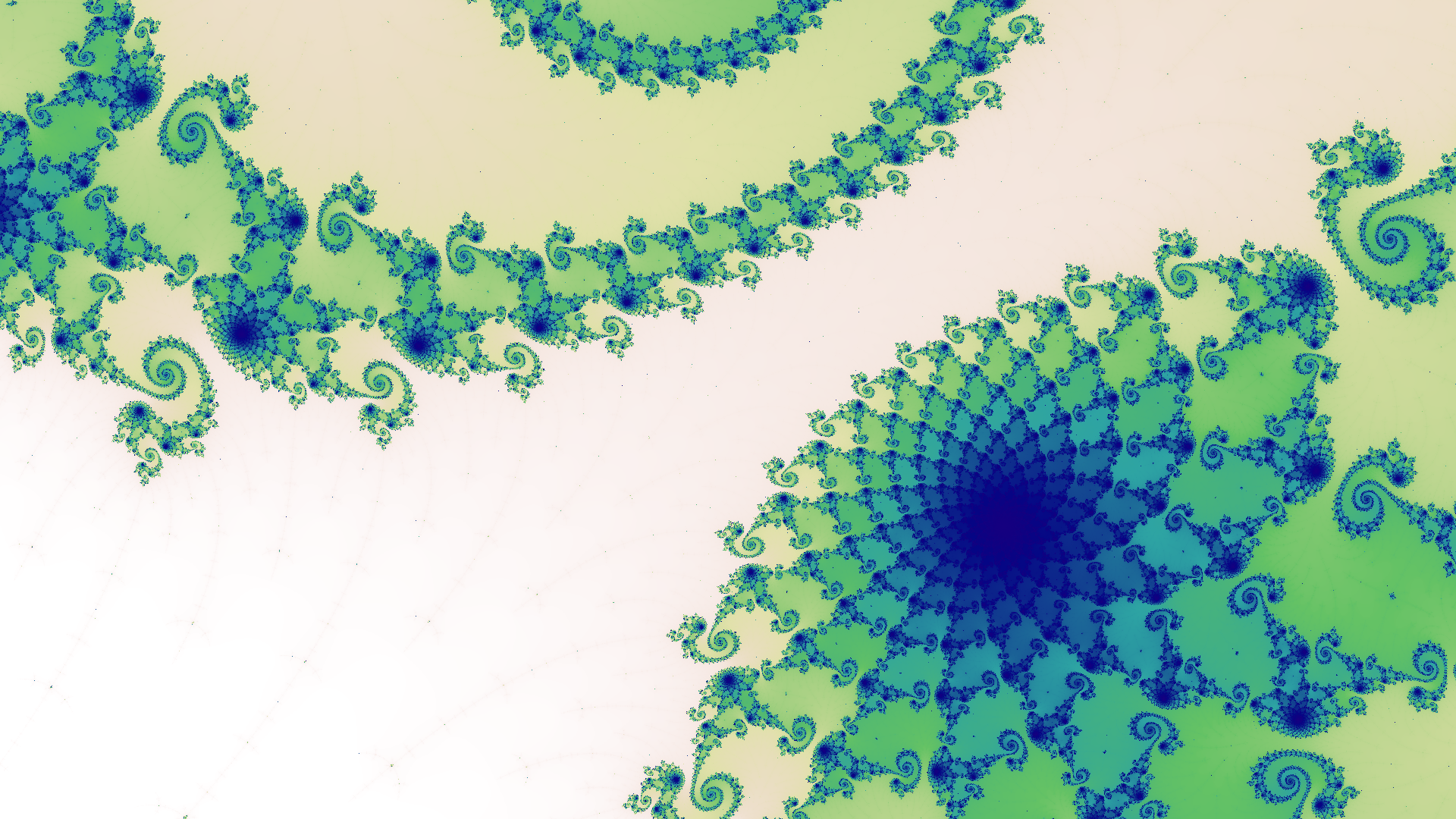

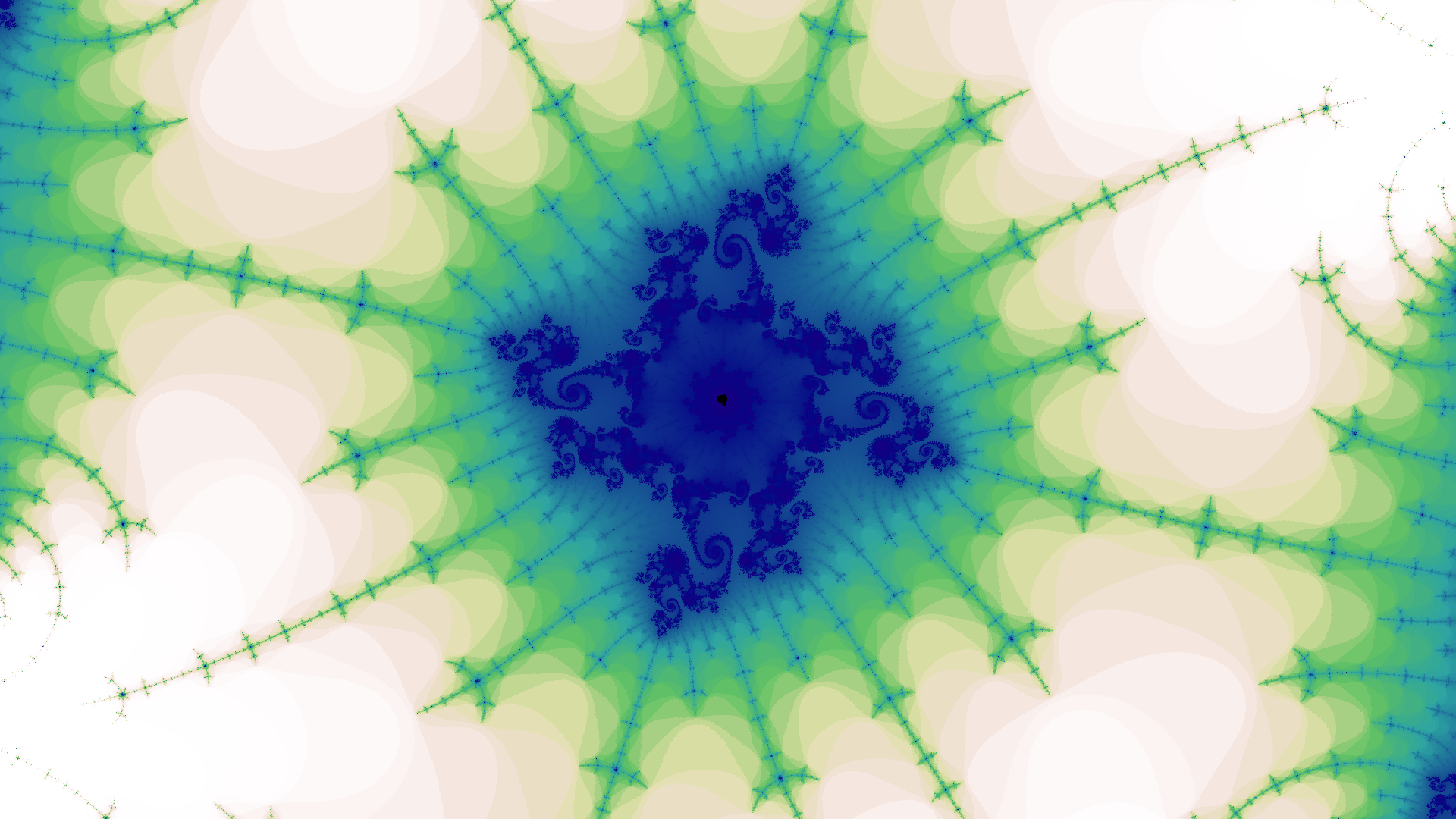

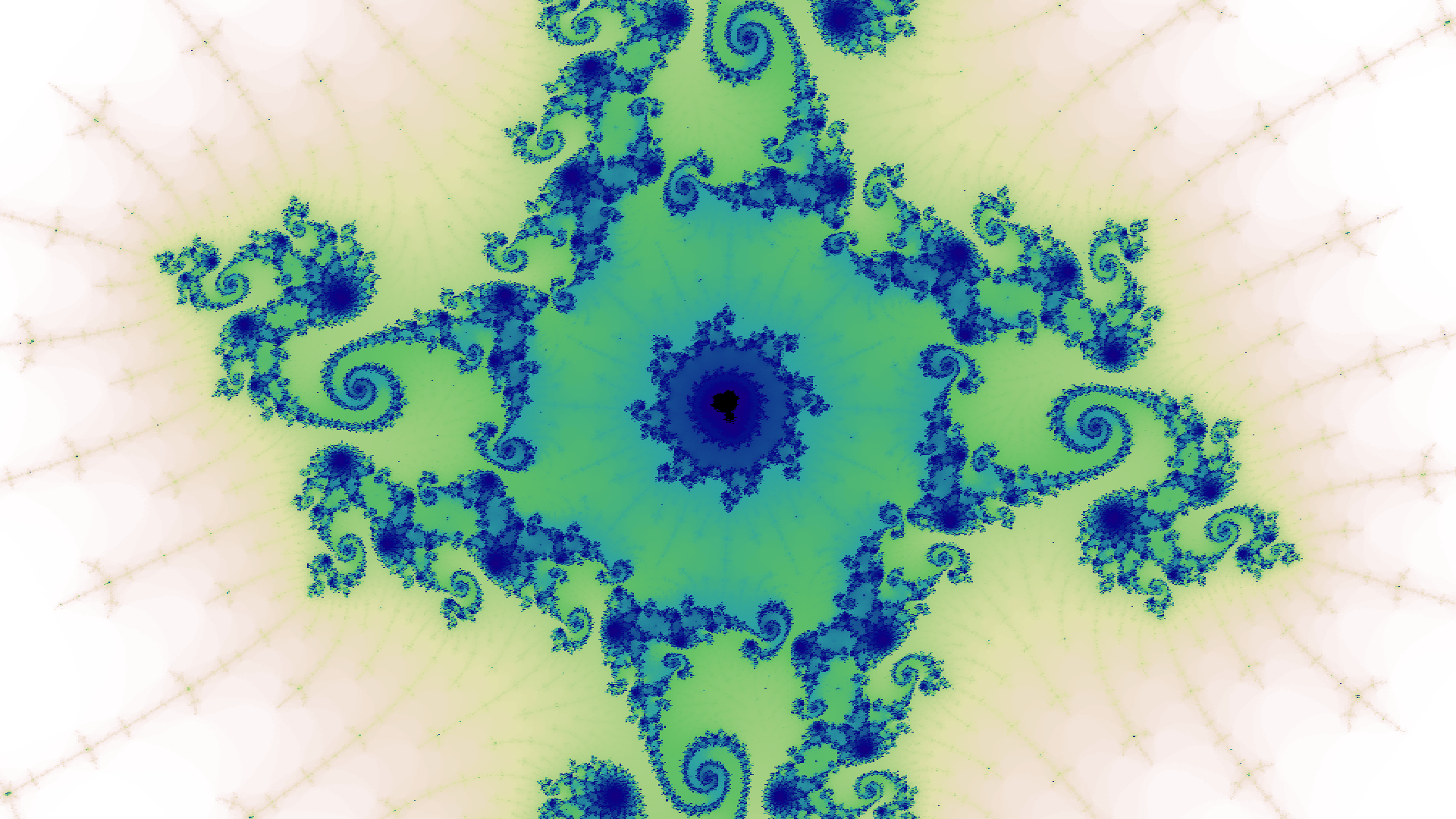

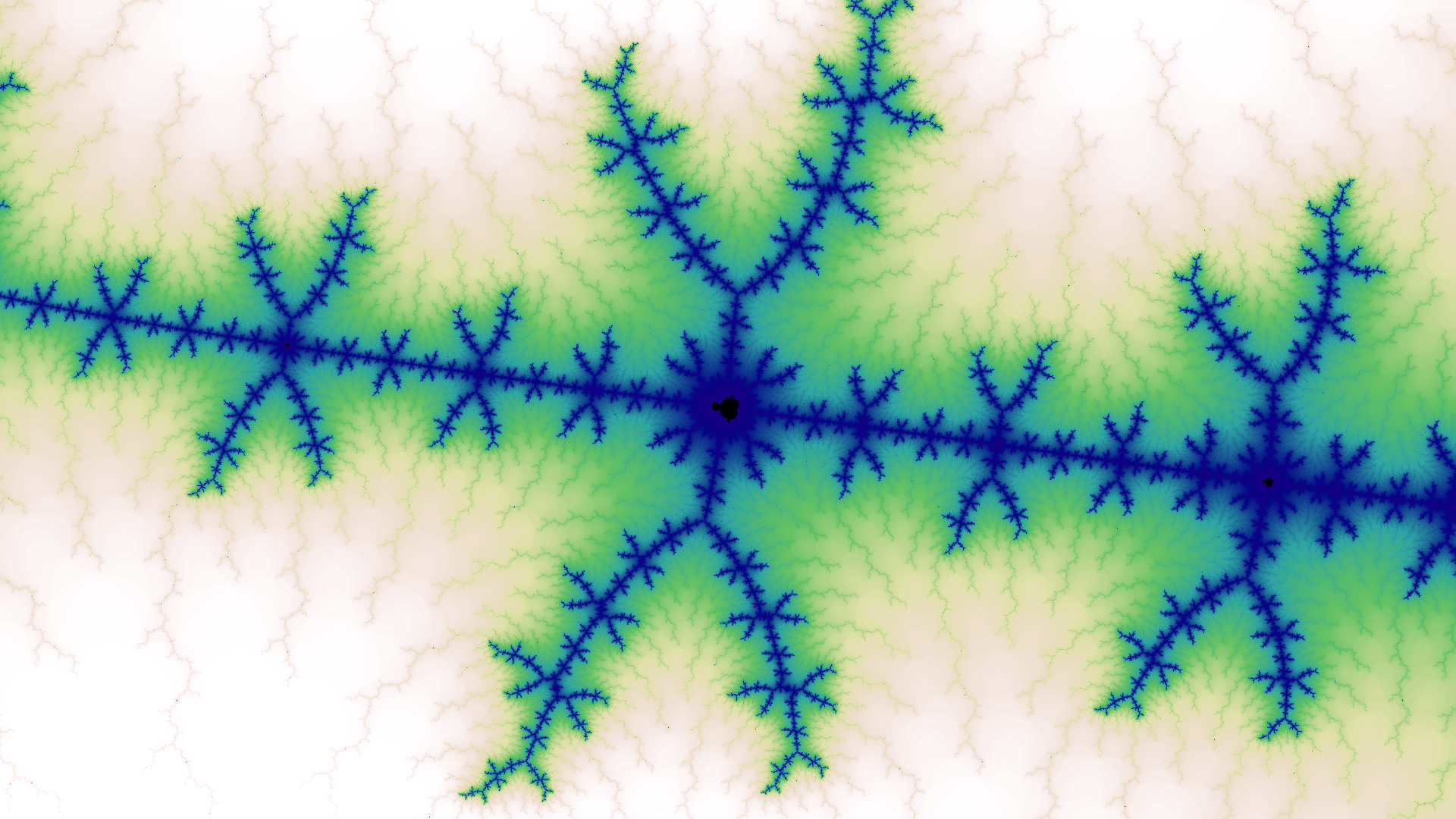

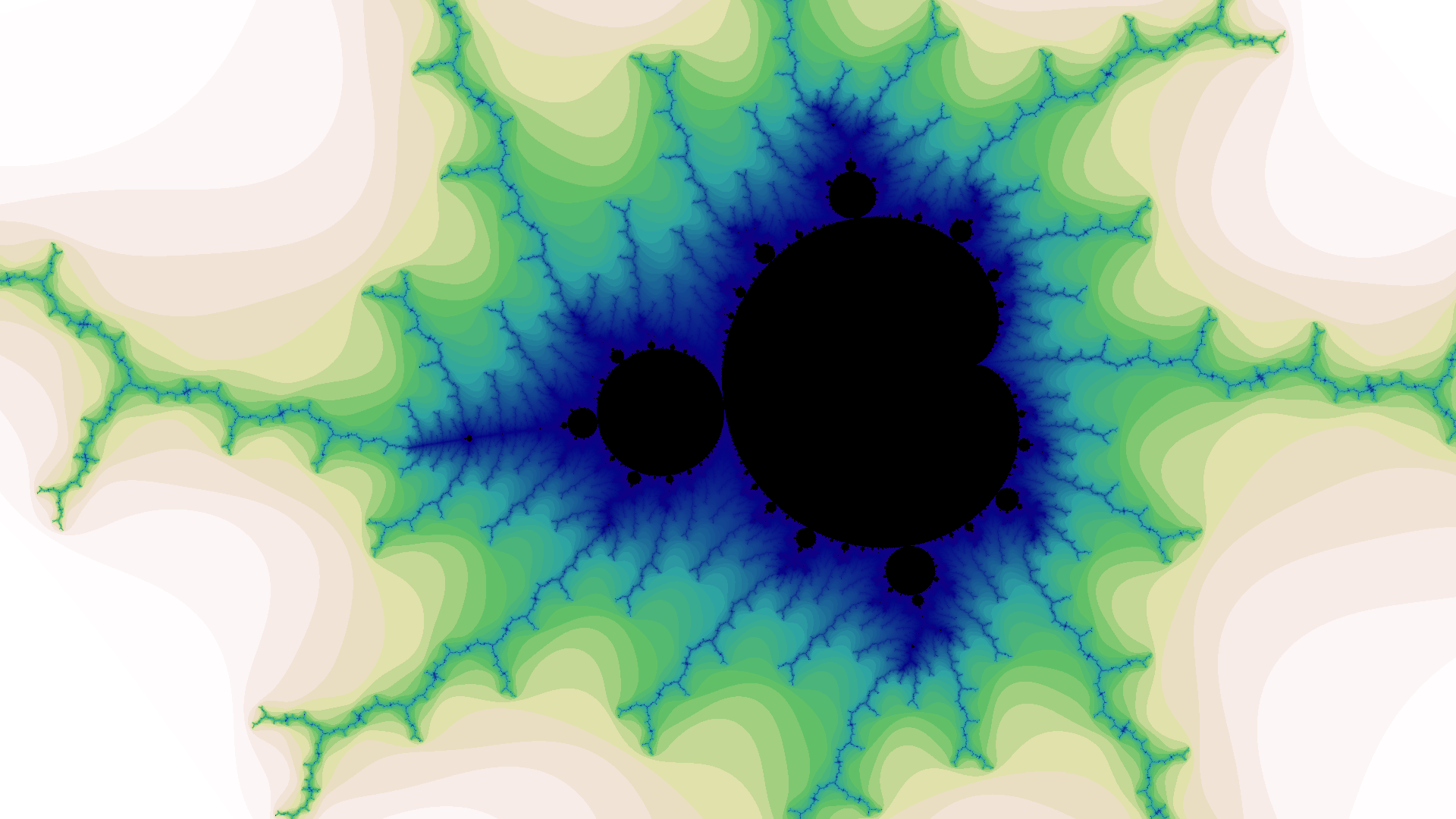

I was particularly drawn to the uncanny beauty and complexity of the Mandelbrot set, which is the complex values \(c\) for which the iteration \(z \gets z^2 + c\) does not diverge when starting with \(z = 0\). This is so simply stated1, and yet generates the images below, revealing endless variations of complexity as you zoom deeper into the set.

Early Difficulties

Over the years I made several attempts to generate these images myself, on the various workstations and PCs I had available at the time. But ultimately it was frustrating because each image took so long to compute that it was painfully slow to explore to any depth in the Mandelbrot set.

The reason for the long compute times is that for each of the \(c\) values of a million or so pixels you need to iterate \(z \gets z^2 + c\) until it is diverging (\(\lvert z \rvert > 2\)). That can be fairly fast for pixels not in the Mandelbrot set (displayed with a color according to how many iterations). But for pixels that are in the Mandelbrot set (displayed as black), they will never diverge, so you have to pick some maximum number of iterations before giving up and deeming it to be non-diverging. The big problem is pixels that are outside the set but very close to it: they might require a large number of iterations before they diverge, especially at high zoom levels. To get a reasonably accurate set boundary you need the maximum iterations threshold to be at least 1000 at moderate zoom and 10,000 or 100,000 at higher zooms. Thus you can easily be doing billions of complex-number calculations per image.

In the end the computers I had available at the time were just too slow.

Trying Again

During the 2020 Winter Holidays I started thinking about generating Mandelbrot sets again, for the first time in more than a decade.

I realized that one thing different was that even my now several-years-old Linux ThinkPad laptop was vastly faster than anything I tried using before, especially if I could use all eight cores in parallel.

The first question was what programming language to use. To get the performance I wanted, interpreted languages like Python and JavaScript were out of the question, and I also thought that VM languages like Java or a .Net languages probably would not give me the control I wanted. So that left the choices:

- Rust is on my to-do list of languages to learn, but it was more than I wanted to tackle over the Holidays. Also the memory-safety features, which are the big advantages of Rust, while important for large-scale programming are not so important for this rather modest application.

- Go would have been fine, but in my past experience that libraries for graphics and color handling are fewer and harder to use than for C++.

- C++ is what I ended up choosing. Carefully written it can be faster than anything except possible assembly-language programming (and I was not willing to go down that rathole)

The only other performance option I considered was to investigate using GPU computation – but I decided to leave that for another time.

As a first quick prototype preserved in the now-obsolete SDL branch of the code on Github I used the SDL graphics library to throw up a window on my laptop and set pixels.

int iterations(int maxIterationCount, const complex<double> &c) {

complex<double> z = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < maxIterationCount; ++i) {

z = z * z + c;

if (abs(z) > 2) {

return i;

}

}

return maxIterationCount;

}

The C++ code takes advantage of the convenience of being able to use the

std::complex type which means that the code z = z * z + c looks pretty much

like the mathematical expression \(z \gets z^2 + c\).

The code uses double which I’ve found allows zooming down to widths of

\(10^{-13}\) before obvious numeric artifacts appear. A possible future

extension of the project would be to use arbitrary precision math to allow

deeper zooms.

int threadCount = thread::hardware_concurrency();

void threadWorker(const Params ¶ms, Image *img, int mod) {

for (int iy = mod; iy < params.imgHeight; iy += threadCount)

for (int ix = 0; ix < params.imgWidth; ++ix) {

img->iterations(ix, iy) = iterations(params, ix, iy);

}

cout << "Finished thread " << mod << endl;

}

...

vector<thread> threads;

for (int mod = 0; mod < threadCount; ++mod) {

threads.emplace_back(threadWorker, params, &img, mod);

}

for (auto &thread : threads) {

thread.join();

}

I also made sure I was using all available processing power by running multiple threads in parallel, which was easy because each pixel can be calculated independently. The threads interleave which rows they are working on:

The good news was this experiment showed reasonable performance, generating megapixel images in seconds.

However this prototype had no UI (it had hardcoded parameters) so I needed to figure out how to put a UI on it. What I chose was a web app that operates as follows:

- The user opens a URL with the parameters encoded in the URL hash parameters.

- The client JS decodes the parameters and sets the

srcattribute of the<img>tag to a URL that invokes the server JS. - If the image file for these parameters has not already been generated, the server JS invokes the C++ binary, which generates the image file and writes it out to the server’s static files directory.

- The server JS sends back a 302 response to the client, redirecting it to the the static URL for the generated image file.

- The client JS updates its UI, and its hash parameters (enabling browser forward and back history to work).

- The user chooses some parameters and clicks on somewhere in the image.

- The client JS updates the

srcattribute of the<img>tag according to the updated parameters to update the URL that invokes the server JS. (goto step 3)

app.use(express.static('public'))

app.get('/image', (req, res) => {

const { x, y, w, i } = req.query

const imgPath = `/cache/mandelbrot_${x}_${y}_${w}_${i}.png`

const imgFileName = `public${imgPath}`

if (existsSync(imgFileName)) {

console.log('Using existing cached ', imgFileName)

res.redirect(imgPath)

return

}

console.log('Generating ', imgFileName)

const ls = spawn('./mandelbrot', [

'-o', imgFileName,

'-x', x,

'-y', y,

'-w', w,

'-i', i,

'-W', imgWidth,

'-H', imgHeight

])

ls.on('close', code => {

console.log(`child process exited with code ${code}`)

console.log('Generated ', imgFileName)

res.redirect(imgPath)

})

})

The server-side JavaScript code is very straightforward. It provides one

endpoint for serving the static image files and a /image endpoint for invoking

the C++ binary and redirecting to the generated image file:

let busy = false

const setCursorMagnification = () => {

const magnification = magnificationElement.valueAsNumber

zoomElement.innerText = 1 << magnification

imgElement.className = `cursor-${magnification}`

}

const setIterations = () => {

const i = Math.pow(10, iLog10Element.valueAsNumber)

iNewElement.innerText = i

}

const doit = () => {

if (!window.location.hash) {

window.location = '#0_0_8_1000'

}

const [x, y, w, i] = window.location.hash.substr(1).split('_')

xElement.innerText = x

yElement.innerText = y

wElement.innerText = w

iElement.innerText = i

busy = true

imgElement.className = 'cursor-busy'

imgElement.setAttribute('src', `/image?x=${x}&y=${y}&w=${w}&i=${i}`)

imgElement.onload = () => {

setCursorMagnification()

busy = false

}

imgElement.onclick = event => {

if (busy) {

imgElement.className = 'cursor-error'

setTimeout(() => {

if (busy) {

imgElement.className = 'cursor-busy'

}

}, 200)

return

}

const { offsetX, offsetY } = event

const scale = w / imgWidth

const height = scale * imgHeight

const viewPortLeft = x - w / 2

const viewPortTop = y - height / 2

const newX = viewPortLeft + offsetX * scale

const newY = viewPortTop + (imgHeight - offsetY) * scale

const magnification = magnificationElement.valueAsNumber

const zoom = 1 << magnification

zoomElement.innerText = zoom

window.location = `#${newX}_${newY}_${w / zoom}_${iNewElement.innerText}`

doit()

}

}

window.onload = () => {

window.onhashchange = doit

magnificationElement.onchange = setCursorMagnification

iLog10Element.onchange = setIterations

setIterations()

doit()

}

The client JavaScript code has the plumbing to pass down the parameters

from the HTML to the server via the image URL query parameters. It also has a

simple mutex mechanism using the busy Boolean to prevent the page spawning

more than one concurrent image generation, and to modify the cursor to let the

user know the state.

Results

Click any image to see in full resolution, \(1920 \times 1080\), which is suitable for use as a video-conferencing background.

-

Though it is a bit more complex when the complex numbers are decomposed into their real and imaginary components: \(z \gets z^2 + c\) expands to \(z_{re} \gets z_{re}^2 - z_{im}^2 + c_{re}\) and \(z_{im} \gets 2 z_{re} z_{im} + c_{im}\) ↩